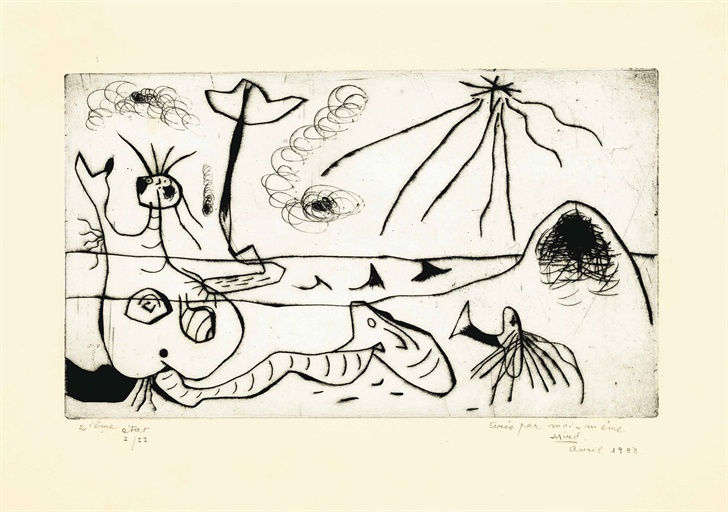

The world looked to Spain. The Spanish Civil War had begun in 1936 when Francisco Franco and the fascists attempted to overthrow the Republic under Manuel Azaña. Spain’s great artists collected in Paris in 1937 to display solidarity behind Azaña and the Republicans. Joan Miró, till then a mostly apolitical spectator, put The Reaper on the wall of the Spanish Pavilion at the Paris World Fair, publicly declaring his loyalty to the Republican cause.

The large mural symbolically depicts a man wearing the cap of the Catalan peasant with a sickle, a crude weapon, and a clenched fist, the salute of the Republicans. All that survives of the work are pictures. The mural was lost or destroyed in the years following the World Fair.

Miró never seemed upset by its loss. Picasso’s Guernica overshadowed the work in the eyes of critics of the time, and because of this the world did not yet understand its great loss. While Picasso depicted a tragic and horrific vision of the war and also reality, Miró depicted a defiantly optimistic vision of the Spanish people and humanity. Though the cause that Miró was fighting for would be defeated by the Nationalists, his vision of defiance and strength persist.

Joan Miró had been living between Paris and Spain since 1920. He had become deeply entrenched in the intellectual and artistic world of Paris that flourished in the 1920’s and 1930’s. One of his most acclaimed works, The Farm (1921), a half-Cubist and half-Realist painting depicting his Catalan countryside, includes a French newspaper, a nod to the influence of Paris on his work and thought.

It was while Miró was working on The Farm that he met Ernest Hemingway in Paris. The two would box after long days of painting or writing. The piece took Miró nine taxing months to complete, but Hemingway saw the value of the piece, picking up shifts as a grocery clerk to buy it. Hemingway held onto the painting for the rest of his life. “After Miró had painted The Farm,” Hemingway would say, “and after James Joyce had written Ulysses, they had a right to expect people to trust the further things they did, even when people did not understand them.”

A visit to Picasso is like visiting a ballerina with a number of lovers…

– Joan Miró

Miró viewed his life in strict moral terms, “I have seen exhibitions of moderns. The French are asleep. Rosenberg Exhibition. Works by Picasso and Charlot. Picasso very fine, very sensitive, a great painter. The visit to his studio made my spirit sink. Everything is done for his dealer, for the money. A visit to Picasso is like visiting a ballerina with a number of lovers…” Miró’s individualism and strong moral vision pushed him away from some of the dominant artistic labels of the time, and in retrospect it is a glaring omission on Breton’s part to have left him out of his surrealist manifesto of 1924.

Miró was also noted for his obsession with order and structure. Jacques Dupin, Miró’s biographer, wrote, “I have often seen him bent over a sheet of paper, and flick off a grain of dust that has just alighted on it: each time the practiced gesture is just the same. Nothing is left to chance, not even in his daily habits: there is a time to take a walk, a time to read, there is a time to be with his family and there is a time to work.” For a man with a profound insight into the subconscious, his life is highly ordered. He seemed capable of the difficult task of balancing the intellect with the emotions.

Only these two traits combined as they are in Miró could produce the artwork that he did. Miró was a man who held his own truths. He did not cater his work to the public, and his work contains an emotional intensity that is matched by a penetrating intellect, a meticulous method, and complete self-discipline.

Miró was a man who would have been content working his trade, living in peace. But the era that he lived in demanded a different life than the one he envisioned. Miró had a strong attachment to his country, compelling him to act toward its defense. Miró raised his voice and his fist and stood against the fascists when he painted The Reaper, showing the great moral responsibility of the artist in political crisis. Miró was asked late in his life what he had done to oppose Franco and the fascists. His response, “Free and violent things.”

Miró’s artwork has only risen in its value over the last decade as the world has begun to understand the significance of his artwork. In June of 2012, one of his pieces, Peinture, sold for 23.5 million pounds. Please contact us if you would like more information about the work of Joan Miró or any of the other fine artists available at Surovek Gallery.

References:

news.artnet.com/market/market-spanish-artist-joan-mirc3-just-keeps-growing-297840

wikivisually.com/wiki/The_Reaper_(Mir%C3%B3_painting)

www.theartstory.org/artist-miro-joan-artworks.htm

www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-joan-miro-pioneer-surrealism

www.pablopicasso.org/picasso-and-joan-miro.jsp

www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/mar/20/joan-miro-life-ladder-escape-tate