In 1983, Tom Wesselman wanted to reduce his drawings to their most basic lines, not with paint, but with steel. He wanted them to feel like they had been lifted off the canvas to form three-dimensional works that were both painterly and sculptural; sculptures that look as though they were drawn on the wall.

One of the problems he faced, in 1983, was the lack of technology that would enable him to cut the steel into the forms that he envisioned.

Laser cutters were not widely available in the 1980s. The idea of using a laser for cutting was first proposed by Albert Einstein in 1917. His theory of “stimulated emission of radiation” was just just a theory, until 1960, when Theodore Maiman, an American engineer and physicist, created the first working laser. Maiman used a synthetic ruby to generate a deep red beam. His invention was met with skepticism and described as “a solution looking for a problem.”

In 1964, Kumar Patel, an electrical engineer at Bell Labs, who thought that Maiman was on to something, invented a gas laser cutting process using a carbon dioxide mixture that was more efficient than the ruby laser. His colleague, J.E. Guesic, invented the crystal laser process later that year.

It wasn’t scientific journals or technical writings that popularized their process; it was Hollywood. The crystal laser process was featured in a famous scene in the 1964 film Goldfinger, where the villain explains the effectiveness of the laser and then attempts to cut James Bond in half with its beam.

Wesselmann began hand-cutting aluminum for his works and then met with metalworks fabricator, Alfred Lippincott, to develop a method that could cut steel with the care and precision that the works required.

His reaction to seeing his first laser cut work was one of elation, “I anticipated how exciting it would be for me to get a drawing back in steel.” he said, “I could hold it in my hands. I could pick it up by the lines, off the paper. It was so exciting. It was like suddenly I was a whole new artist.”

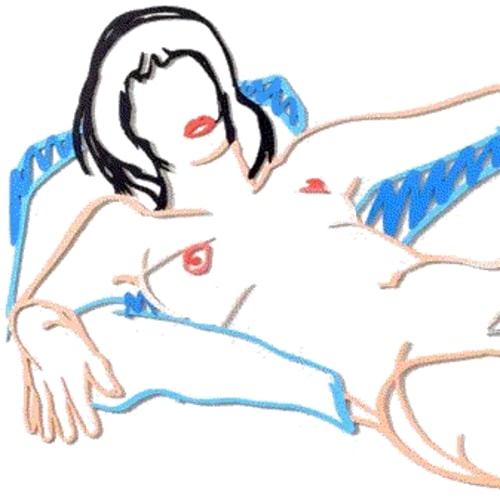

The first of his steel works were done in black and white and, as his technique progressed, he worked in color. Monica Lying on Blanket, 1988, a recent acquisition at Surovek Gallery, exemplifies Wesselman’s idea of drawing as sculpture.

Wesselmann called his works Steel Drawings. After the Whitney acquired one of the works in 1985, he was sent a letter asking him why he called them drawings and not sculptures. He responded by saying that he considered it a pure drawing and “an example of life not necessarily being as simple as one might wish.”

References:

Cultured Magazine. 19 Years Later, Peek Inside Artist Tom Wesselmann’s Untouched Studio. May 5, 2023.

Danielle St. Peter. Tom Wesselman Finds a New Medium. Denver Art Museum. July 16, 2014.